This blog was created as an outlet for some of my written work. I have also used it to record a few of my other activities. Hopefully people will find it interesting or useful. I was going to call it – democracy, peace and love – because that’s what I’m most interested in. However, I decided on revolts now in memory of my first zine, revolt now, produced during my high school years. At that time I thought of revolution as an event, but now I think of it as a historical process, a long series of varied events in the past, present and future. The name revolt now had already been taken but revolts now was available. So here it is.

Wollongong Flooded: With Kindness

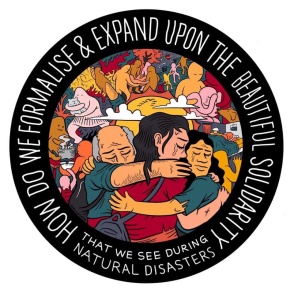

For many years, I’ve been writing about how people and communities respond to disasters. Hopefully I’ll have a book about this published later in the year. In this post, I have put together a few reports about the recent disastrous flooding in various suburbs of my hometown of Wollongong to highlight the widespread kindness, care and solidarity at the heart of individual and communal responses to this and other disasters. On Saturday April 6, I was woken at 5am by the sound of heavy rain and torrents of water pouring down the roof of our house. Forecasters had warned that a storm was coming and here it was. Peering through the window using a torch, I could see our street had become a river and water was rapidly rising in the front yard. Soon it began seeping in through the back door. By the time I got some sandbags from the garden shed, the water was almost up to my knees. To my relief the sandbags did their job and wading back to the front door in the dark my main concern was lightning striking close by. Back inside, I dried myself off and stood in the loungeroom staring at the wall, worrying, once again, about what to do in the face of intensifying disasters. Elsewhere in the city many people were facing much worse, while also discovering they didn’t have to do so alone.

That day, parts of the Illawarra region received more than twice the average April rainfall in less than 24 hours, with all of the local weather monitoring stations topping 200mm. More than 100mm fell between five and six am. As the Illawarra Mercury reported; “That hour became a terrifying nightmare for Gary and Bronwyn Hart, in Lachlan Street at Thirroul, who were woken by their neighbours warning them to ‘get out!’ “It was just after five o’clock and everybody was in bed when we got a knock on the door from our next-door neighbour saying that the creek had burst its banks and flooded,” Mr Hart said. “But then, I don’t know whether it was rocks or the pressure of the water, but the whole front of the house, the wall was just gone, and everything came through the house. We’ve got glass sliding doors at the back of the house and all the furniture got pushed by the water and the mud against that door. It built up and built up and then the door shattered. The whole inside of the house is just gone. We couldn’t get out back or front, the water was all around us.” As the water raged through their home, Bronwyn got caught in the force of it and was knocked over. As she fell, Gary desperately hung on to her. She was almost washed away, possibly forever.

Elsewhere in Thirroul, Jemima Macdonald and her family had only moved into their new home a fortnight before disaster struck. Jolted awake by the sound of neighbours banging on their door, they found floodwater pouring into their home. “We knew we had to get out immediately. We didn’t grab anything, just our son.” Returning later to a scene of utter destruction, their home and yard completely submerged – “It was just devastating to see all of our stuff ruined.” Especially since the family don’t have flood insurance and Jemima’s partner has recently been made redundant. Shocked by the impact of the flood, it was the response of others that lifted their sprits, as neighbours and the wider community rallied around them. “We had neighbours, people from the other side of Thirroul coming over and bringing their shovels and mops and saying what can we do, where do we start?” she said. “Or not even asking us, just going in and doing it because we didn’t know where to start. We didn’t know a single person when we moved in, and we moved here to be part of the community and that is what we got.”

On the other side of town, Mount Keira residents were confronted by a huge torrent that broke the banks of Byarong Creek and lifted a backyard cabin off its foundations, then swept it through the neighbour’s backyards. According to local resident, Paul Harrison; ‘It then careened down to a nearby bridge at horrendous speed, slammed into the bridge and broke apart. Two people were still inside when it slammed into the bridge.” Neighbours from across the road saw it, were able to get over there and help them get out. The rescued pair were eventually taken to hospital but had luckily escaped with minor injuries. When the sky cleared, neighbours from around the creek brought their gumboots and a helping hand, dragging the debris from affected people’s backyards into the street and began to tidy-up what they could.

Nearby, as Kealsie Beavis left her home in Figtree that morning it was pitch black and the chest-high floodwaters were making dangerous rapids outside, as a car floated by before slamming into a house. Standing at her front door clutching her baby in one arm, she used the other arm to pass over her three-year-old son to her neighbour, Nick, as he fought to stay upright in the raging water churning around him. Her son looked back at her as he was taken into the darkness, his rescuer holding tight to a rope tied to a telegraph pole across the road as the floodwaters threatened to take both of them down.

Another rescuer soon appeared and took her dog to safety. Then, Nick came back to rescue her daughter. It was still dark outside, and cars were now rushing by in the floodwaters, threatening to knock them both over in the debris filled mess. “I was terrified … letting both your children go is really hard and really scary,” she said amid a flood of tears. “Then it was just me, I didn’t want anyone else to be in danger. I said ‘don’t put yourself in danger to try and get to me’. I couldn’t live with someone else being hurt.”

The water and mud wrecked most of the family’s possessions, the oven, dishwasher, fridge, washing machine, TV and most of their other stuff. But as Kealsie saw it; “Lots of things have been damaged, but that can all be replaced, I’m not worried about that. Everything’s replaceable but we are not, we’re safe and that’s the main thing.” What was also important she explained to a reporter, is “I love where I live. It’s a very lovely community and it’s got a very good community feel about it and we’ve got really lovely people surrounding us.”

Elsewhere in Figtree, Ric Stalenberg woke up and walked onto his front verandah to see a neighbour’s car floating down the street. After the flood, he described the street as looking like a war zone. “You can barely drive down the middle of the road and you can barely walk down on either footpath because it’s piled up with furniture and white goods and carpets clothes and mud.” A young couple in the flats next door got out with only the clothes on their backs. They lost everything else, all their electrical goods, all their furniture and carpet, clothing – everything. Ric was shocked by the flood, but he was also struck by the “community spirit”, when people rallied around to help those in need. This included a communal clean-up effort and one of those involved asking the local pizza shop “the whole of Arrow Avenue is shovelling their lives away – is there any chance you could help us out with 10 pizzas?’ To which the response was ‘is ten enough, how about twenty? You can have as many as you need and if you need more come back and get them.’

In North Wollongong, soon after the flood, almost everything Claire Dewhirst, her young son and their housemate, Jodie Pearce, owned sat stacked in waterlogged piles outside the house they once called home. They were left with nothing except the clothes on their backs, a couple of handbags, their pet rabbits and dog. They have had to vacate their rented home and Jodie, a family daycare educator, is now without work and income as she ran her daycare from the house. Nor did they have renters’ contents insurance because, being in a flood zone, it was much too expensive. In response to their situation, Suzy O’Keefe, the mother of a child who attended Jodie’s daycare, immediately established a GoFundMe to help them get back on their feet. In the week after the flood, the fund had already raised thousands of dollars.

On Bellambi’s Pioneer Road, Brett Marriage woke up to water around his ankles. “I didn’t hear anything until a neighbour knocked on the door saying: ‘are you OK?'” He is OK, but his carpet and doors are damaged beyond repair, the recently installed kitchen will probably need replacing and his car is likely to get written off “because it looks like a Christmas tree when you turn it on.” However, the most devastating loss for Mr Marriage, was more personal, reflecting the fact that when disasters strike people often don’t worry as much about many of their possessions as they do about their relationships with loved ones. “My dad passed away last year and there was some sentimental stuff that was under my bed. There’s nothing we can do about it, but that’s what I was spewing about mainly,” he said.

Nearby, as Luke Murray got up, he saw water coming through his front door. It was “like a waterfall down the driveway coming into my house.” Realising the water needed somewhere to escape to he broke down his backyard fence so the water could flow out. Afterwards, to help dry his home, he was given industrial fans by some friends of friends and also received support from the gym he goes to. “Everyone’s helping each other,” he told the media, while their reports on the flood’s impacts in Bellambi also highlighted how a “silver lining of the situation has been the efforts of the local community banding together to help each other out.”

In Woonona, Susan Jarnason also woke up early to the sound of heavy rain. So, she “went downstairs to see there was a metre and a half to two meters of water coming into the bottom level of the house covering everything”. Susan’s neighbours barely knew who she was, yet it didn’t stop them from helping her clean-up afterwards. She had only moved into her home less than a month ago, but as she reported; “The neighbours in this block have been absolutely phenomenal. They were here all day yesterday comforting, cleaning, moving dirt, feeding us, watering us – everything that could possibly be done.” While another Woonona flood casualty, Penny Wilson, also voiced her appreciation for the community’s caring response; “People were walking past saying ‘can I help’, ‘can I bring something down, ‘can I bring a mop’,” she said. “Everyone was pitching in to help,” including a coffee truck offering people free coffee and the local kebab van giving away food to those helping out.

Importantly, this sort of widespread compassion, care and kindness is the most common response to such disasters. Even though many people are cynical about humanity, believing that people tend to be selfish and greedy, disaster responses provide plenty of evidence to the contrary (Here and here are some more examples from the recent floods in Queensland). When we take a cynical view of people, it’s easy to miss the widespread kindness that exists around us. Of course, selfishness is socially powerful and a key feature of capitalist society. We are often taught to be self-centred and selfishness is fostered by those seeking to disempower and exploit people, to divide us and to pit us against each other. But kindness, love, and care are more powerful. And in the face of intensifying disasters, we need to grasp the importance of cooperation to human development and that most people tend towards solidarity, crave togetherness, and yearn for connection. As a local journalist reporting on one of the streets featured above explained; “The flood has changed this little street, the neighbours are checking in on each other and by late Sunday afternoon they shared cans of beer amid more tears and hugs as they wonder what to do next.”

With climate change transforming the world and more storms, more floods, more fires, more disasters on the way, what did this one suggest about what we should do next? Well, we should focus less on possessions and more on people’s safety, lives and relationships. And to help deal with disasters we should reach out to, assist, support, comfort, and share with each other. Sure, some people respond to disasters in horrible ways, and we can’t always rely on those around us at the time, neighbours, family, friends, or caring strangers. But when disasters strike, we may need to rely on them, and they are the most likely to be ‘first responders’. Crucially, people and communities that foster kindness and value social solidarity are likely to be the most helpful and resilient in the long run.

So, now I’m staring at my screen, wondering what more can be done in the face of intensifying disasters and what’s standing in the way of us doing what needs to be done. So, my next post – Flooding the Zone with Shit will also be about the flood, but here I will focus on some of the crap that inundated Wollongong along with the water, as well as the responses to the flood from those in positions of power.

Nick Southall

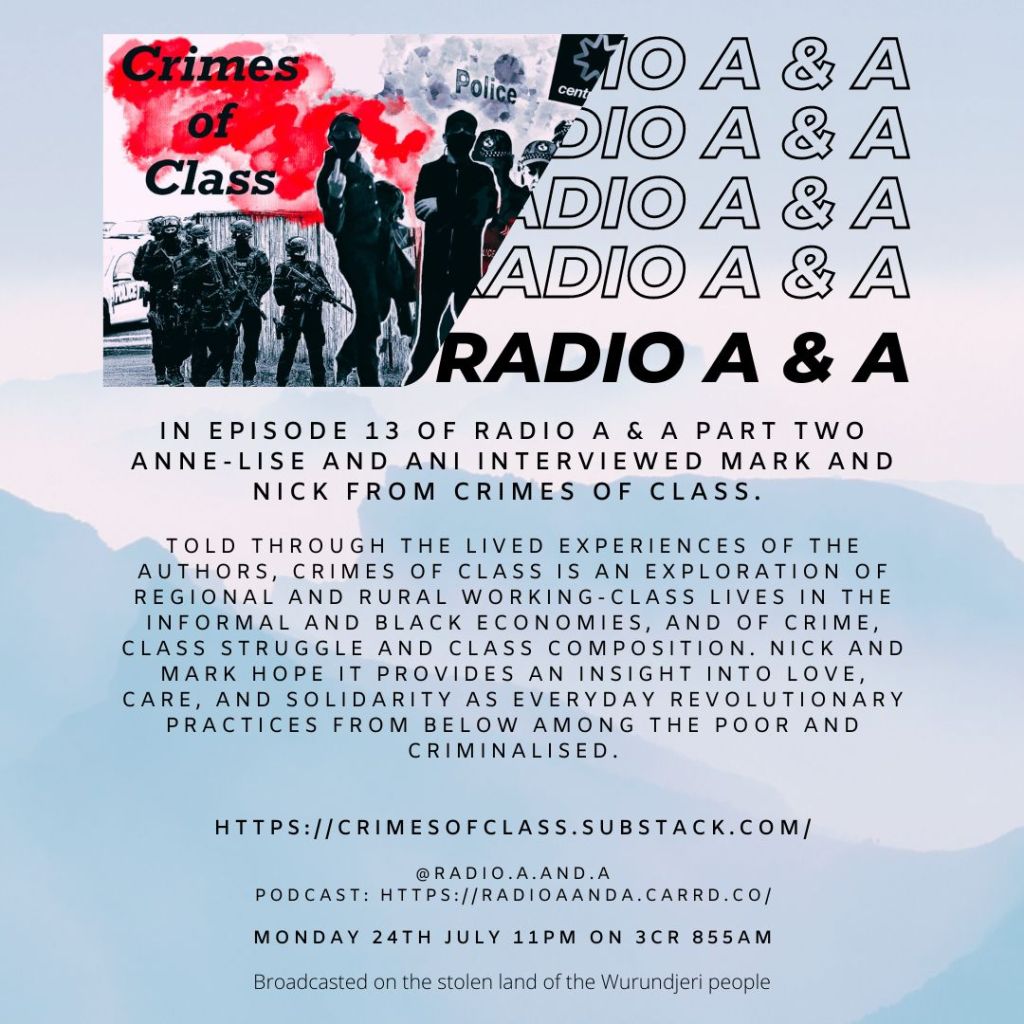

Radio A & A – Crimes of Class

Recently, Mark Gawne and I were interviewed by Radio A and A on 3CR Community Radio, about our Crimes of Class blog, which I have previously posted about. The hosts, Anne-lise and Ani, talked to us about community and individual responses to harm, transformative justice, accountability, safety, support and healing, within and challenging dominator culture. The interview engaged with themes raised in Crimes of Class, but also delved into new questions that we hadn’t explored or covered explicitly.

A big thank you to Anne-lise and Ani for taking the time to talk with us and have us on their show. It was a really interesting discussion, challenging us in thoughtful and beneficial ways.

You can listen to Part 1 & Part 2 of the interview, which aired in June/July 2023, here

https://www.3cr.org.au/satelliteskies/episode/radio-and-episode-12

https://www.3cr.org.au/satelliteskies/episode/radio-and-episode-13

If you haven’t seen our Crimes of Class blog – it’s an exploration of regional and rural working-class lives in the informal and black economies, and of crime, class struggle and class composition. Here Mark and I interview each other and consider love, care, and solidarity as everyday revolutionary practices from below among the poor and criminalised – https://crimesofclass.substack.com/p/welcome-to-crimes-of-class?utm_source=profile&utm_medium=reader2

The ‘Cost of Living’ & Work Refusal: Gong Commune ‘Firestarter’

On Monday, September 26, 2022, Gong Commune held an open public discussion about contemporary crisis and the cost of living. The event was organised into four sections based on the questions –

1. What do the ‘Great Refusal’ and other struggles around work tell us about capitalism today?

2. What is inflation, what is driving it, and why is it happening like this now?

3. What is going on in the public sector struggles and why are they important?

4. What can we do to improve our lives together in the near and far term?

Each question was briefly addressed by a ‘fire starter’ speaker to help launch the discussions. I was asked to give a brief response to the question – What do the ‘Great Refusal’ and other struggles around work tell us about capitalism today?

Here’s my response.

Discussions about economic crises usually focus on the power of capital, the growing miseries of poverty while profits soar, or austerity budgets like the one Labor is preparing us for while they cut rich people’s taxes. But I prefer to explore the struggles against capitalism and to think about how the ruling class reacts to our power. Importantly today this power is evident in the struggles against capitalist work, such as the global ‘great refusal’, ‘great resignation’, ‘great retirement’ and the decentring of economic values due to increased concerns for health, safety, and care.

Given the recent past, we need to consider how powerful and profound the impacts of the pandemic have been and continue to be. So, perhaps we can start thinking about these concerns in relation to the term – ‘the cost of living’. ‘The cost of living’ tends to suggest that we measure life in economic ways, focusing on money, finance, debt, prices, rent and wages. Of course these are all important. However, the class struggles of the past decade have increasingly focused on health, safety, care, our relationships with each other, with the world around us, on human life and the existences of other living things. These struggles suggest other ways of thinking about ‘the cost of living’ and pose profound questions about capitalism as a system in crisis – questions like – Is the ‘cost of living’ that millions of people, especially the most vulnerable, must needlessly die? Or – is it a ‘cost of living’ that we destroy the environmental basis of life? As it becomes clear that for much of the ruling class and for capitalism in general the answer to these questions is apparently ‘yes’, why should we, why would we, want to work to reproduce this system?

The basis of capitalist society is the enforcement of work for capital – ensuring that most people, most of the time, are engaged in the daily reproduction of exploitation; in production, distribution and consumption for profit, for the benefit of the ruling class. It often appears that we have little power and it can be hard to appreciate the power we do have. While the power of workers is indicated by strikes, pickets and other industrial action, much of our resistance to capitalist work and shit working and living conditions tends to be invisible, neglected, or ignored. In recent years though, especially during the pandemic, the power of work refusal in various forms has been more widely recognised. For example, at the start of the pandemic, many workers stayed at home or refused to go to work before state movement restrictions were announced, forcing governments and businesses to implement health and safety measures – including increased welfare payments and subsidised wages.

Across the world billions of people have continued to refuse to work in the way they used to, have changed the way they work, and have questioned and challenged what they work for. Work refusal is in the air, anti-work forums are increasingly popular, social media is widely used to encourage various forms of work refusal and the pandemic has changed the way many people think about the time and value of their lives. Yet, although the ‘great refusal’, ‘great resignation’, and ‘great retirement’ have received a lot of attention, most work refusal doesn’t involve leaving your job. Instead, it includes refusing both paid and unpaid work in a more general and often in more micro senses – slowing down, avoiding certain tasks, doing a half-arsed job, staying away from work, taking sick days when you’re sick rather than ‘soldiering on’, or spending work time doing things you want to do. While what today is called ‘quiet quitting’ might appear to involve relatively insignificant individual acts, these acts are being taken by billions of people to exert power over what they do, how they do it, why they do it, and whether they do it.

Most work refusal is relatively ‘quiet’, yet when it’s widespread and commonly practiced it contributes to louder forms, which receive more attention. Today, many workers are refusing work by striking – especially in industries where large numbers have refused work by resigning – such as nursing, aged care and teaching. These strikes have highlighted the financial ‘costs of living’ and low pay because economic crisis forces more and more people to push back, positioning workers as struggling for increased wages. Yet strikers have also focused on health issues, staffing ratios, workplace and public safety, decent working conditions, exhaustion, burnout, and the psychological costs of working.

Meanwhile, bosses and governments are powerfully reacting to the popularity of work refusal. Inflation, high interest rates, low wages, poverty welfare benefits, rent hikes, and price rises are attacks on our standard of living which bosses use to discipline workers, to discourage work refusal, and to encourage people to work more and harder, forcing those who are insecure into greater insecurity and those who have built-up some savings as a protective buffer from insecurity to spend their savings and end-up insecure. The increased focus on paying debts, on inflation, on price rises, on rent, frames the ‘cost of living’ as about economic concerns, centred on ‘the market’, money, economic growth, productivity, efficiency, and profitability. This decentres the ‘costs of living’ in relation to the future of life on earth, the health and safety of people, our quality of life, our social connections, or the care crisis; in aged care, physical and mental health care, child care, social care and environmental care. Still, importantly, the pandemic has given many people more time and more reasons to think deeply about the state of the world and many are refusing to return to ‘business as usual’. Instead, they are seeking to live as if their lives matter and their actions count.

So, to conclude, some questions I’m wondering about are – given the intensifying costs of capitalism, how can we take back more of our time so we can focus on what’s most important? As capitalism descends into a deepening series of crises, how can we permanently transform our lives? How can we more effectively refuse capitalist work and organise our own collective power – so that living isn’t costly?

You can find notes from the other ‘fire starter’ responses and a recording of the event on the Gong Commune website here.

ABC Radio interview: From Sheffield to The Gong

On August 23 2022, it was announced that a major long-term expansion of the local Dendrobium coal mine wouldn’t be going ahead. This was a significant victory for the local, regional and global environmental movements, including Protect Our Water Alliance (POWA), the main group coordinating opposition to the project. Earlier this year, I wrote about this campaign in Coal Struggles: ‘The past we inherit, the future we build’. During that morning, as I was celebrating our win over global mining corporation South32, I was asked to have a chat on ABC Radio Illawarra with Lindsay McDougall (of punk band Frenzel Rhomb fame). The interview wasn’t about the environmental campaigning victory, although we did discuss it and that day’s announcement influenced what I focused on during our conversation, but was instead part of a series of interviews Lindsay has been doing with people who migrated to Wollongong from other parts of the world. For those who may be interested, here’s the edited version which went to air that afternoon –

Crimes of Class

Earlier this year (2022), Mark Gawne and I began publishing our Crimes of Class project in instalments on Substack. Told through our lived experiences, Crimes of Class is an exploration of regional and rural working-class lives in the informal and black economies, and of crime, class struggle and class composition.

The two of us started talking about this project because of a brief discussion we had on social media about stories from back in the day, the oral history of political movements and everyday life, and the moral instructions of social movements alongside our experiences in the informal and criminal economies. We discussed writing about our experiences before deciding to begin by interviewing each other. We came up with some fairly open questions, with the idea that we would respond to each other’s questions and then follow-up, hone them, and come back and ask more questions. The two interviews with each other are based on this process.

So far, Crimes of Class includes two long-form interviews, which were published in short sections at semi-regular intervals. We hope the interviews provide some useful insights into love, care, and solidarity as everyday revolutionary practices from below among the poor and criminalised. After receiving positive feedback and encouragement, we are currently considering what we will do next with this project.

You can find Crimes of Class here – https://crimesofclass.substack.com/p/welcome-to-crimes-of-class?utm_source=profile&utm_medium=reader2

Communes

This work was originally published in November 2021 as an article in Gong Commune’s zine Communes: Past, Present, Future, where you can find the full contents.

In this post I consider communes as a range of social relationships; communes as ways to oppose and demolish capitalism, to live differently within it, and to escape it. The word commune has been used to describe a variety of radical communities. Historically, we can point to examples like the Paris Commune, to ‘hippy’ and alternative lifestyle communes, or the contemporary proliferation of revolutionary communes in South America. This year (2021) marks the 150th anniversary of the Paris Commune and the celebrations in the ‘city of love’ are called ‘We the Commune’ to commemorate the “glorious harbinger of a new society” and those who “came together to take their destiny into their own hands”. Meanwhile, here in Wollongong, we seek to listen and learn from hundreds of years of Dharawal and Yuin struggles for self-determination, community, and Country and millennia of communal knowledges and practices embedded within the Aboriginal custodianship of Country.

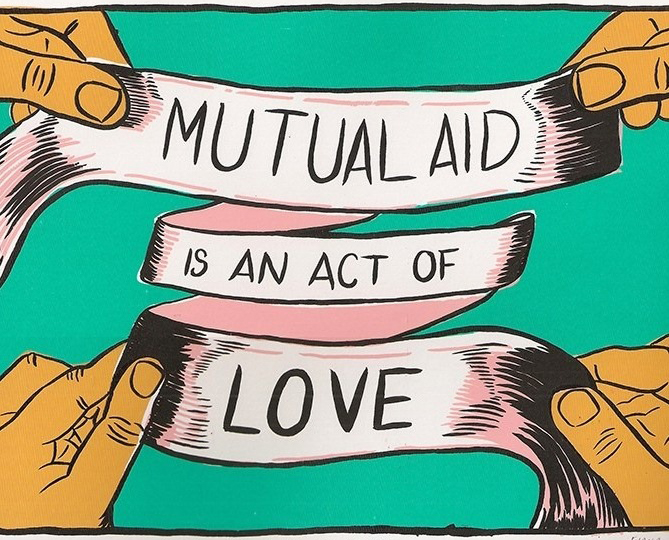

Communes are created by people’s ongoing acts of invention, innovation, meeting, working, and organising together. They involve a multitude of places and interactions that are continually being formed and transformed, creating space for efforts and associations in which more democratic politics can be experimented with. Communes can include social solidarity during crises and disasters, strikes, picket lines, radical and progressive organisational spaces, meetings, protests, occupations, public assemblies, celebrations, homes, squats, community gardens, autonomous collectives, and more, where people working together to refuse and dismantle the exploitation and oppressions of capitalism, colonialism, and patriarchy, seek to support the broadest possible freedom for all.

Communes tend to operate beyond or on the fringes of money, markets, and commodities, where the re/production of life’s necessities is generally approached as a common struggle to redistribute social wealth, to provide people with what they need based on the collective ability to support each other. These reciprocal relations are not measured in work hours or wages, but in valuable relationships that motivate each person to do what they can do and need to do to re/produce and extend both small and large scale communes. Yet, while communes are not centred on cash, debts, or private property, neither are they pure. Communes often require money to cover costs, to purchase resources, and to share with those in need. So, communes remain intertwined with the social relations of capitalist society and are riddled with contradictions and ambiguities.

Large and small, short-term and long-lasting, local communes draw strength from the vibrant history of radical social movements, social solidarity, and diverse communities working together to address common concerns within this region and beyond. Today, Wollongong is full of people caring for friends, family members, neighbours, vulnerable people and environments, for little, if any, financial reward. They are involved in cultural activities, social movements, justice campaigns, community groups, civic and leisure activities, in building different worlds with alternative forms of production, distribution, and consumption.

Communes produce different ways of living based on pluralist networks and involve a range of decentralised experiments in collective self-government and complex decision-making procedures. By creating more democratic connections between individuals, organisations, campaigns and movements, people can work together in a manner where no person or specific struggle is seen as necessarily more important than any other, where all can be valued.

Communes create emotional resources, psychological spaces, and social environments that pay attention to other people, to living things, to what is important in life. They arise from social cooperation, where action is grounded not in possessions but in interactions with and openness to others. Where activity is not centred on having but being-with, acting with, creating-with. Where work, skills, resources, assets, knowledges, experiences, histories, cultures, goods, what we produce together, is shared.

Communes promote new ways of thinking – journeys of self and social discovery. The needs and desires for radical change spark a growth of consciousness raising, radical education, independent research, media, and cultural production – including alternative news and analysis, arts events, gigs, performances, rebel music, bands, choirs, blogs, reading groups, films, videos, writing, poetry, comedy, storytelling, theatre, online debates, and discussions. These practices are part of widespread cultures of caring, resistance and revolt which include indigenous cultural practices, care for Country, a range of protest cultures, the cultural practices of community organisations, political groups, unions, and social movements, mutual aid, gift cultures, and repair cultures.

In Wollongong, a number of contemporary social movements involve a deep questioning of the purpose of work and production. Forging slower-paced and more leisured communities, many people are today rediscovering the importance of fun and joy, while questioning the purpose of their work and the sacrificing of their health and lifetime for careers, possessions, and a heartless system. They are developing ways to survive that minimise capitalist labour, to thrive in opposition to capitalist institutions, to help unleash people’s power and potential.

The community solidarity cultivated by collectively organising our own activities, our own production, our own services, our own events, generates more meaningful bonds and makes life more rewarding. The development of many and varied ties of affection and comradeship among people, where an individual’s endeavours and achievements rely on the web of friendships and caring relationships which sustains them, encourages long term involvement in projects that are making a real difference, in creative, mutually beneficial activities, in tasks that make people’s lives better, that benefit the community, and the environment.

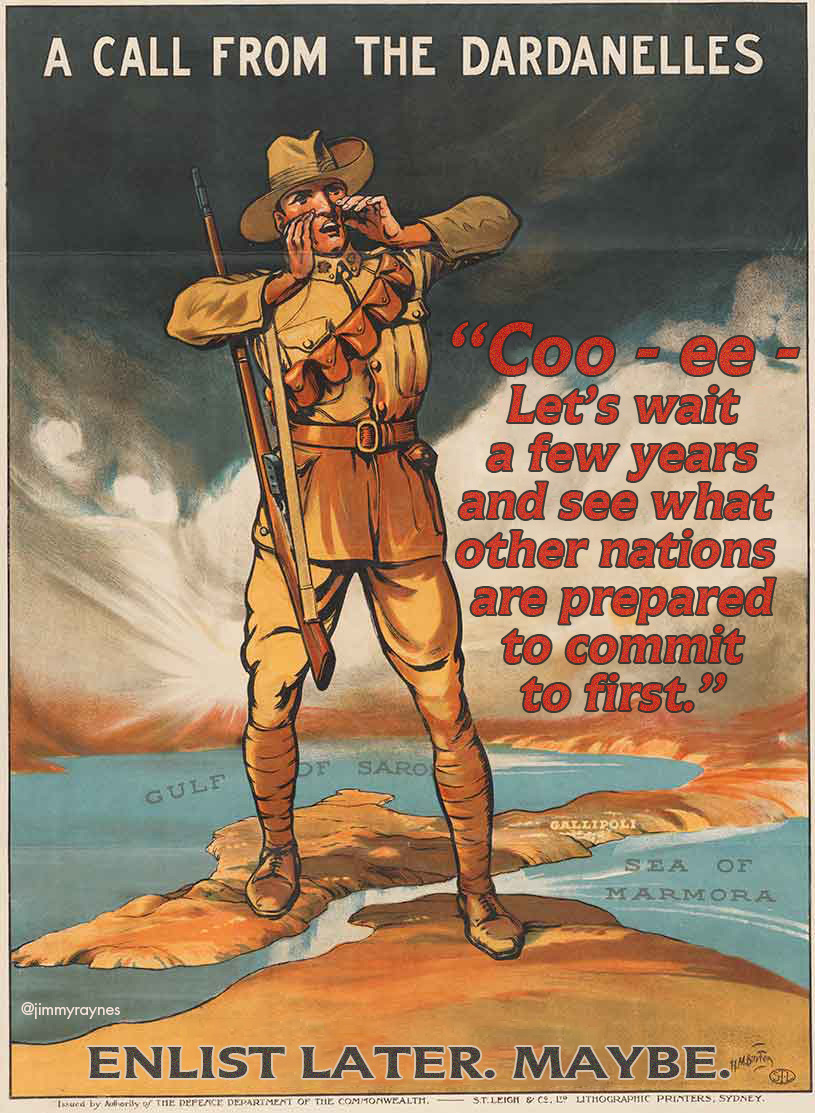

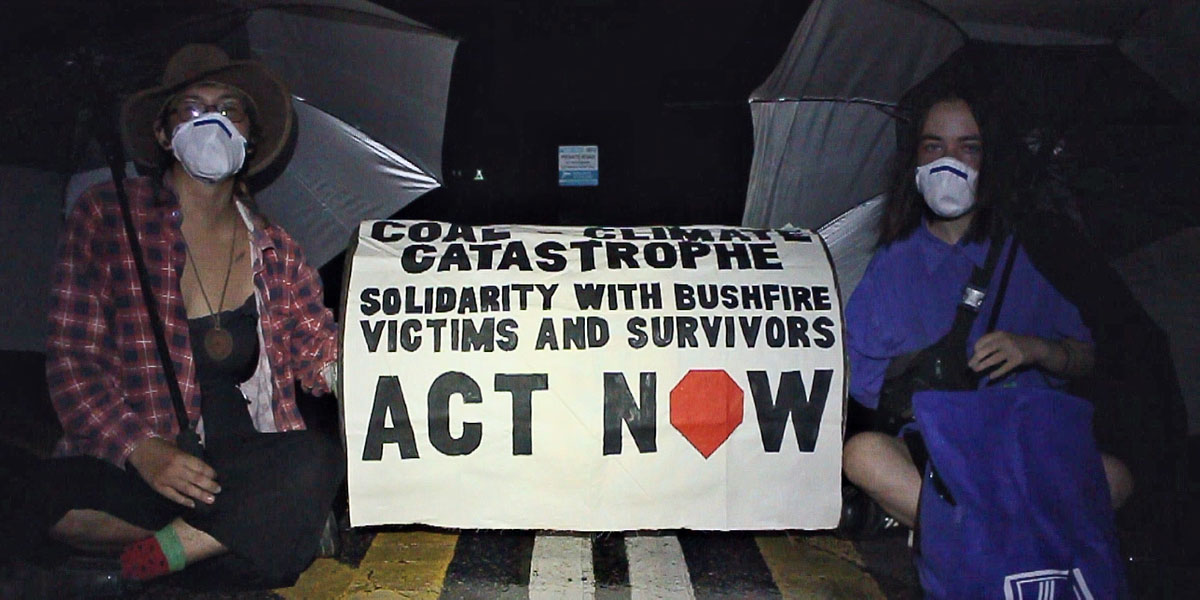

In the past couple of years, we have seen the construction of powerful local communes to organise climate strikes, actions to shut down the Coal2020 & Coal2021 conferences, community mobilisations to halt the expansion of mining under the local water catchment, Black Lives Matter protests, and ongoing intricate webs of mutual aid, illustrating the power and potential of overt and unseen communal organising. Significantly, communes focused on the environmental, climate, and extinction crises have increasingly become a spanner in the workings of local fossil fuel infrastructure, countering ecological destruction, and corporate dominance, while continuing to develop a growing network of alternative production, distribution, and exchange experiments. Many thousands of people doing thousands of activities have been making these things happen, as part of an upsurge of local, national, and global activism.

The hugely successful 2019 Climate Strike in Wollongong, with more than 5000 people participating, relied on an organising process that actively involved a wide cross section of individuals and groups with an array of political perspectives. Those taking part mainly put aside areas of disagreement and instead concentrated on their commonalities and the tasks required to organise the Strike. Having a variety of activities and actions helped to encourage a diversity of tactics and strategies, the development of autonomous organising, and a focus on the interconnections between local and global concerns. Rather than creating conflict and competition between those wishing to do different things, there was a flourishing of experimentation and a breadth of activity, fostering empowerment, encouraging solidarity, and accommodating differences. In this way local activity generated space for broader political debates concerning the movement’s composition, the effectiveness of different actions, strategies, and tactics, while encouraging inventive approaches.

Following the Climate Strike, the Illawarra Climate Justice Alliance (ICJA) began circulating a call-out for people to travel to Wollongong to help ‘shut-down’ the Coal2020 Conference at the University of Wollongong (UOW) through protests and pickets. The Conference had been held at UOW as an annual event bringing together mining companies, industry experts and scientists for the previous 19 years, to discuss the best ways to find, dig, package, sell, ship, burn, and profit from coal. Due to the planned protest actions the Conference was called-off only weeks before it was scheduled to happen. This was the first time the University was forced to cancel a major coal mining conference, a significant victory and a shot-in-the-arm for the climate justice movement.

Activists from across the Illawarra, Sydney, the A.C.T., and beyond worked together to stop the Conference from happening. In preparation for shutting-it-down, ICJA began to organise billeting and places to camp for those traveling from elsewhere. Posters and flyers were produced and distributed both locally and further afield. Speakers from ICJA attended meetings, the Students of Sustainability Conference and a range of community gatherings, to help publicise the up-coming action. Community information sessions, direct action skill shares, and a ‘Shut Down Coal2020’ discussion for high schoolers, facilitated by high school student members of the ICJA, were planned. A Facebook event was created where information was provided on general plans, the protest events, and advice/assistance for those taking part. Other social media platforms were also used to publicise actions and gain support. Local, state, and national groups helped with publicity and support in the lead-up to the event, mainly through their own networks and via social media. On the UOW campus, members of the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU), other workers, and the Wollongong Undergraduate Student Association (WUSA) supported the protests.

It was anticipated that hundreds of people would take part in the ‘Shut-Down’ actions. This would include people providing logistical support, facilitating a variety of activities, taking part in well-organised or more spontaneous actions, and those blockading in ways that carried relatively more risk of arrest (e.g. near the doors or inside). Different groups would arrange assorted actions, taking responsibility for blockading certain entrances, creating colour, movement, and disruption. Drum groups, musical performances, speeches, and direct actions both outside and inside the venue would deploy various creative tactics. Some of the activities were being coordinated by ICJA, while space was made available for more decentralised and autonomous action – helping to create an unpredictable convergence of diverse yet complimentary participation. The large number of potential participants, their defiance and determination, and the complexity of the planned activities convinced the University to pull the plug, as UOW management voiced concerns about damage to the University’s reputation which would follow heavy handed policing of the community’s attempt to stop the Conference.

Following the cancellation of Coal2020, UOW and the mining interests that sponsor these conferences were forced to flee the region as they began planning to hold Coal2021 at the University of Southern Queensland (USQ). However, our commitment to oppose the conferences where-ever they are held remained. So, we contacted concerned people and groups in Queensland encouraging them to help shut-down Coal2021. In January this year (2021), the Conference website went from public to private and the organisers removed public registration to avoid scrutiny and to stifle community opposition. This was followed soon after by confirmation from USQ and the Ipswich police that the Conference would no longer be taking place at the University. Covid restrictions may have played a part in their decision to cancel, but they were also increasingly aware of the planned protests. Fleeing the Illawarra region, to evade community opposition and the climate justice movement, had failed.

Soon after, the NSW Independent Planning Commission’s rejection of South32’s twenty-five-year plan to expand coal mining at their Dendrobium pit was also a major win for the local, regional and global environmental movements. Once again, thousands of people had taken part in widespread, powerful, and diverse campaigning to halt this development and protect our water catchment. Open, democratic, and rebellious community organising has also been at the heart of this continuing mobilisation.

That local communal practices of defiance and militancy have continued despite the impacts of the pandemic was also demonstrated last June when hundreds of people took part in an illegal Black Lives Matter protest in central Wollongong. Despite a Supreme Court decision banning the protest and a large police show of force, including mounted police, members of the Riot Squad, Dog Squad, and PolAir, to intimidate those participating, hundreds of people assembled, held our ground, spoke out, and marched.

The Covid-19 crisis has also spurred-on a range of local mutual aid practices, with many initiatives conducted by ‘formal’ mutual aid groups, many more undertaken by ‘informal’ groups, and most remaining publicly invisible. This disaster aid has involved people mutually supporting each other, not just some people ‘doing good works’ for others. Mutual aid practices are always widespread, but during and after crises they tend to expand and flourish, as more people rely on decommodified reciprocal caring relationships. In Wollongong during the pandemic, mutual aid practices have especially supported those hit hardest, including the aged, unwell, poor, international students, and famously the crew of the Ruby Princess. Around the world we have seen a multitude of similar responses.

Communes can help us to survive and thrive despite the disasters of capitalism and the more numerous and widespread communes become the greater their transformative power. They offer the opportunity to experiment with new forms of politics which enables people to experience their own personal agency and collective capacities, to construct and experience different social relationships, to build community, friendships, and solidarity networks. Those involved in communes learn how to work with one another, to collectively produce and make things happen, building confidence by relying on each other and fostering their own initiatives. People’s sense of what is possible, what they can do to change their living conditions, is nourished by an eco-system of collective activities and experiences of halting or reducing damage and creating positive social change.

Importantly, trying to enjoy your life doesn’t have to be a way of hiding from reality. It can be a way of changing reality. It can include running away from what we wish to escape, as well as confronting and undoing it. The achievements of our large and small communes are often denied or neglected, but they continue to radiate through our lives, our relationships, and our communities. What communes are and what they do depends on the wishes of those involved and what they are able to collectively accomplish. Making decisions about what we think is important, what we want to do, how to do it, and organising to achieve our aims, creates alternative communities, circulates communal struggles, preserves non-capitalist and anti-capitalist practices, and builds confidence, by making the constructive power of communes more visible.

Nick Southall

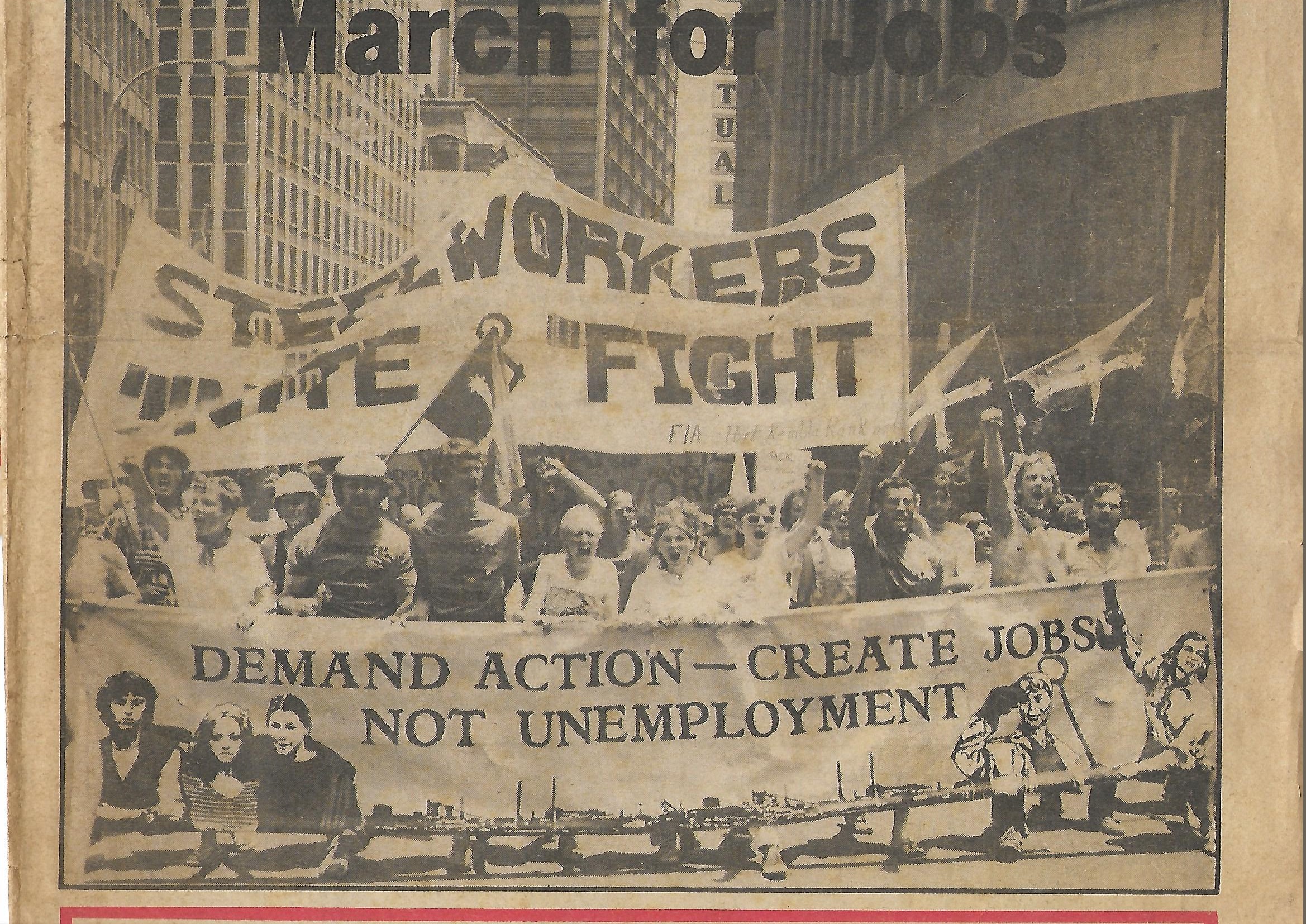

Coal Struggles: ‘The past we inherit, the future we build’

During the 1970s and 1980s, I was involved in many struggles to defend the jobs and working conditions of local mineworkers and those elsewhere. I never considered this a defence of the coal industry, or the wage slavery and dangerous working conditions of miners. Instead, as I said in a recent interview – “We used to struggle to defend the jobs and conditions of miners against attacks from the bosses. Now we strive to protect the environment from fossil fuel corporations, while continuing to advocate for decent jobs and working conditions in the developing ‘green economy’. Campaigning for the closure of local pits and a just transition is still about class power, the fight for justice, the creation of a better world and a brighter future.”

In December 2020, the New South Wales Independent Planning Commission (IPC) held a three day online public hearing into multinational mining company South32’s twenty-five-year plan to expand coal mining at their Dendrobium pit, located in Wollongong. Leading-up to the hearing, thousands of people and a wide range of organisations took part in widespread, powerful, and diverse campaigning to halt this development and to protect the environment and local water catchment. Many of those opposing the extension of Dendrobium made written or oral submissions to the IPC, including myself. In February 2021, in a shock decision, the IPC rejected South32’s expansion application due to what it described as unacceptable impacts on water security as well as biodiversity, threats to ecological communities, and because it would cause serious degradation to watercourses and swamps, release significant amounts of greenhouse gases and cause irreversible damage to Aboriginal cultural artefacts and values. This was a major win for the local, regional and global environmental movements, including Protect Our Water Alliance (POWA), the main group coordinating opposition to the project.

This was the oral submission I made, via Zoom, to the IPC hearings on December 3rd 2020. Most of those making submissions, like myself, were only given a few minutes to speak.

Hello, I’m Dr Nick Southall. I live in Wollongong, I work at the University of Wollongong, and I’m a lecturer in International Development Studies. I acknowledge the indigenous custodians of this land and the millennia of Aboriginal care for Country. I also acknowledge the Illawarra Aboriginal Land Council is strongly opposed to this development proposal. I join their opposition.

South32 admit this proposal will result in a range of irreversible impacts to the water catchment Special Areas, massive loss of drinking water, dangerous effects on water quality, and damage to countless Aboriginal cultural heritage sites. It also threatens ongoing impacts to the climate, the environment, eco-systems and people, including increased likelihood of bush fires on the Illawarra Escarpment.

Large numbers of Australian water experts and the NSW Local Government Association are opposed to mining in the water catchment. Wollongong City Council’s response to the expansion warns of the cumulative loss of water from the extension of this and other coal mines and that those losses will be far greater than predicted. This proposal would significantly reduce local water quality and supplies at the same time as demand increases. WaterNSW say this expansion must not go ahead.

The proposed damage cannot be accurately calculated and may involve the loss of water forever. The damage cannot be repaired and South32’s offer of compensation for the loss of water cannot address the value of a priceless resource. Water is essential for sustainable development, critical for healthy ecosystems, and healthy communities.

Water is the primary medium through which we feel the effects of climate change. A recent Bureau of Meteorology report explains how the dehydration of the escarpment will create conditions for a major inferno which could devastate local bush, eco-systems, wildlife, and risk human life. The burning of fossil fuels and the undermining of our water catchment is turning our region into a tinderbox. This expansion would help to guarantee that in the years ahead the Illawarra burns.

Financial accounting cannot measure priceless resources, eco-systems, and heritage sites. But since the focus of those who seek to profit is on money, let’s be clear – the economic gains will go mostly to South32 – while many of the suggested financial and employment impacts claimed by the company, and those doing economic modelling for them, are based on assumptions that do not hold-up to scrutiny.

This proposal is unlikely to provide even medium-term job creation or financial benefits to our community. Consider the example of the local Metropolitan mine – since their recent expansion process began, Peabody’s share price has collapsed, the company is facing bankruptcy, a large number of jobs at the mine have been eliminated and the pit is now being shut down. Meanwhile, this year, South32 has axed around 100 jobs at Appin. While, 250 of South32’s labour hire workers had their contracts terminated. Some of those jobs were readvertised, but with a possible 40% wage cut, and poorer more dangerous working conditions.

Coalmining is increasingly reliant on labour hire and casual workforces. It is delusional to suggest that there’s a stable future in coal jobs and incomes. Our region’s future prosperity lies elsewhere.

Regarding Bluescope’s reliance on South32, I urge the Commissioners to carefully check the accuracy of company claims about the use of Dendrobium coal and alternative supplies. Bluescope’s blast furnace will soon be retired and a decision will likely be made in 2025 about the future of steelmaking at Port Kembla. Bluescope, along with the Federal and NSW governments, and the CSIRO, are now supporting the development of Port Kembla as a green hydrogen hub, including a production facility worth more than $500 million. Meanwhile, Liberty Steel in Whyalla (another customer of Dendrobium) is investing over $1 billion to rapidly produce decarbonised green steel – because this is what global markets will demand.

In conclusion, South32’s proposal is a two-fold attack on our water supplies – undermining them from below and evaporating them from above. No money can compensate for something that is priceless and for destruction which will be perpetual. You cannot offset eco-system and species loss. Coal mining in the water catchment does not offer a guarantee of secure jobs, decent wages, or economic growth. It will cause irreparable long-term damage to our future prospects. Our region must transition to a more sustainable future. This future needs your support, and that support must include protecting the water that nourishes our community, the economy, and our environment. I strongly urge you to refuse this application.

Over the past few years, Protect Our Water Alliance (POWA) has also been at the forefront of campaigning against Wollongong Coal and the expansion of mining at their Russell Vale Mine. In August 2020, POWA organised a protest outside the company’s Annual General Meeting, held in Towradgi. This was the speech I gave during that action.

We are protesting outside Wollongong Coal’s Annual General Meeting in order to highlight that this mining company’s plans are a risk to the environment and to the community. There must be no mining in our water catchment, the region’s water supply must be protected, and environmental destruction has to be stopped. Both the National Parks Association and WaterNSW say that coal mining expansion in the water catchment poses an unacceptable risk to our water resources and should not be allowed. As climate change accelerates, we need alternative forms of development that are not a risk to a sustainable future.

There will soon be a public hearing into the company’s plans to expand its Russell Vale colliery to mine under the local water catchment. Yet, Wollongong Coal has failed to meet its previous water management, workplace safety, and environmental protection obligations. Therefore, their mining expansion project should not be considered. There can be no guarantee that Wollongong Coal is able to fulfill its conditions under any future approval. They do not have the capability to mine responsibly or safely and the costs to the community will exceed the questionable benefits of the expansion proposal.

Wollongong Coal has debts of around a billion dollars, little revenue, a terrible record on ‘environmental compliance’, and its Wongawilli mine was closed last year after the NSW Resources Regulator found safety issues which were too serious for underground work to continue. The company has been suspended from the Australian Stock Exchange and an investigation by the NSW Government into Wollongong Coal’s fitness to operate a mine and work safely was shelved last year, as it was unable to find them ‘fit and proper’. They are increasingly desperate to exploit any opportunity to make some quick money, due to their disastrous situation and the coal industry’s decline.

After decades of wiping out tens of thousands of local jobs, cutting wages and working conditions, and thrashing our land, air and water, the coal bosses have no interest in the people of this city, its future prosperity, or our environment. They only care about their profits. It is becoming clearer that coal mining is a dying industry. Locally this death is indicated by coal companies in crisis, the increased use of contracting and hyper-exploitation of workers, attacks on our eco-systems, and our water supplies. In the past week we have seen a toxic sludge of coal and chemicals poisoning a major local creek. Australia already suffers the legacy of countless poisonous, unrehabilitated and abandoned mine sites, which when they closed down left a range of damages in their wake. We cannot let this happen here. Wollongong Coal’s dangerous plans should now be halted. The Russell Vale mine expansion should never have been considered, and certainly should not be approved. The NSW Government and the Independent Planning Commission must call an end to this fiasco and step-up to protect our water, our environment, and our community.

In late 2020, the IPC gave the go-ahead for Wollongong Coal’s expansion of the Russell Vale mine. However, opposition to this development has intensified and you can find out more here – https://www.facebook.com/StopRussellValeMine

or here – https://stoprussellvalemine.org/

Meanwhile, the NSW Government with the support of One Nation, the Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party, the Christian Democrats, and the Australian Labor Party have now by-passed the IPC decision on South32’s Dendrobium extension and initiated a new plan to expand that mine. Opposition to this new plan is also continuing – https://www.facebook.com/protectourwateralliance/

In January 2022, The New Bush Telegraph published an article I wrote on behalf of POWA about the on-going struggles around mining in the water catchments. You can find it here – https://newbushtelegraph.org.au/coal-mining-in-water-catchments-must-cease/?fbclid=IwAR1Bfc4wds7sF0QRdJTEIf88N33Dt73jPqTtCnBxoFyRAUFRjUy3tR792EY

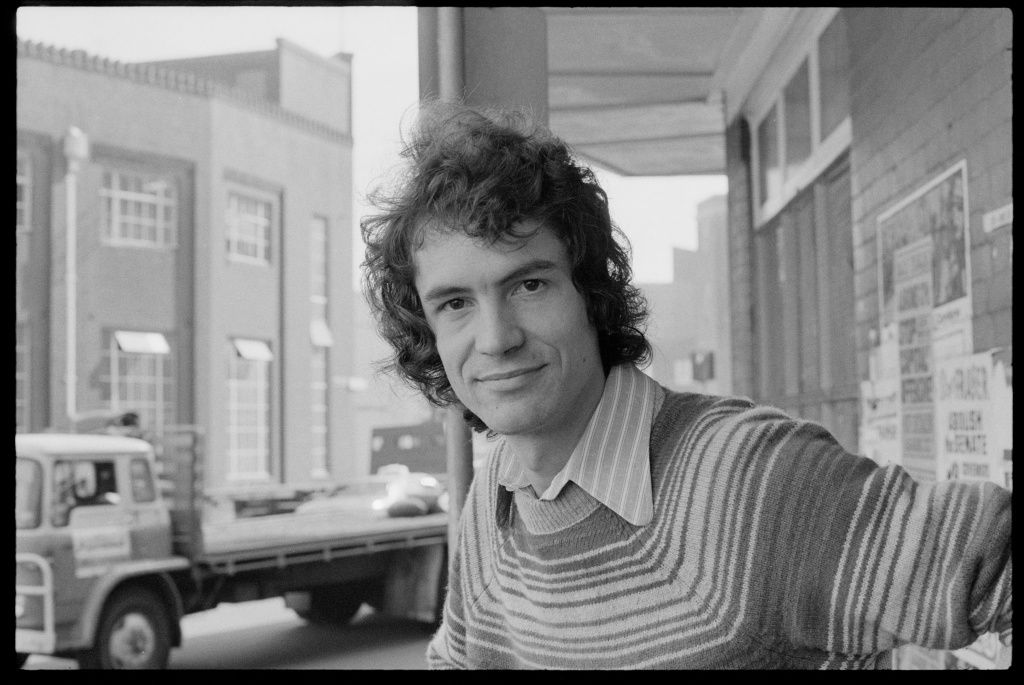

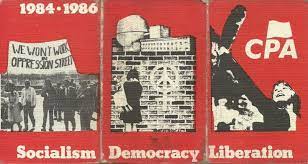

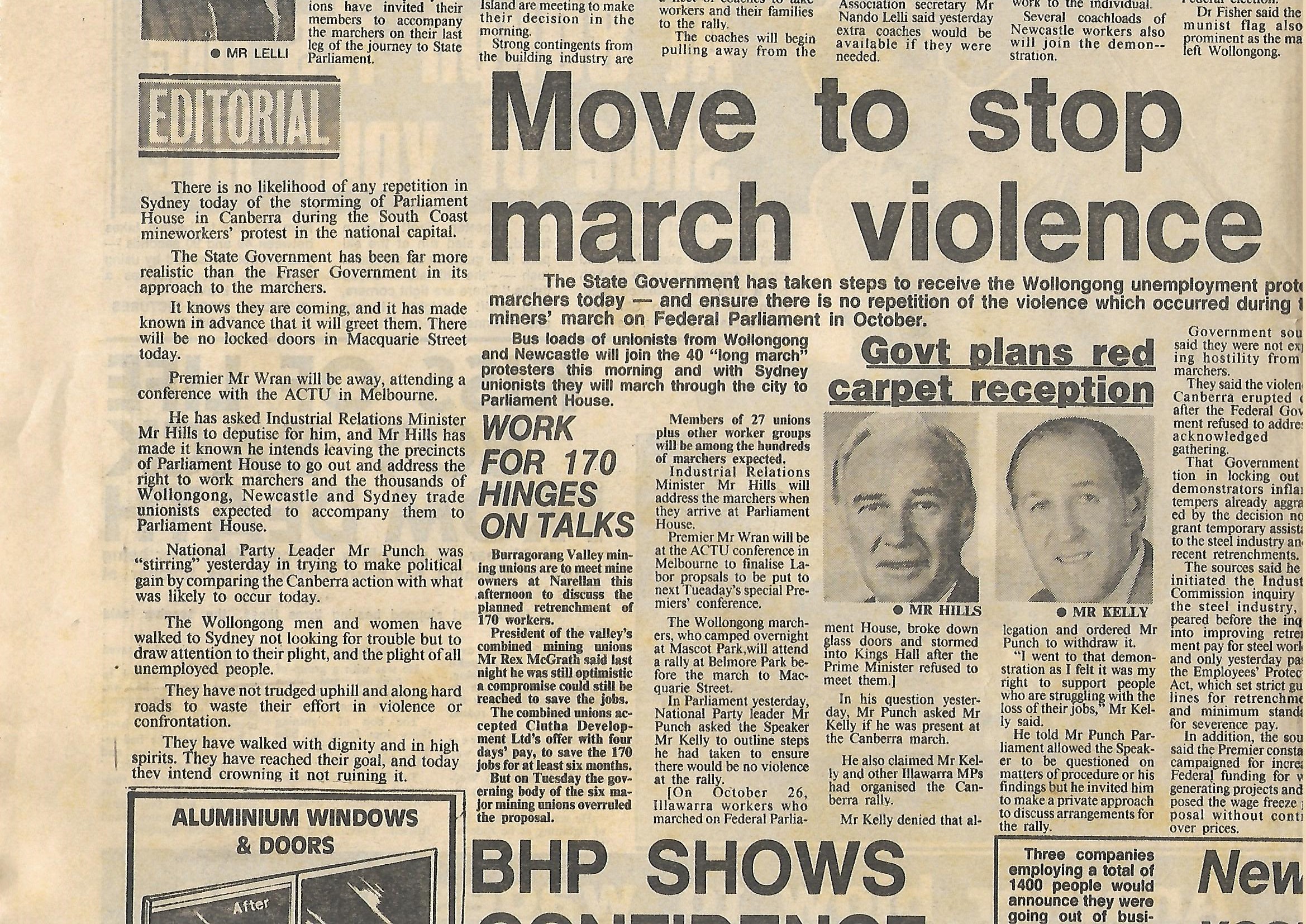

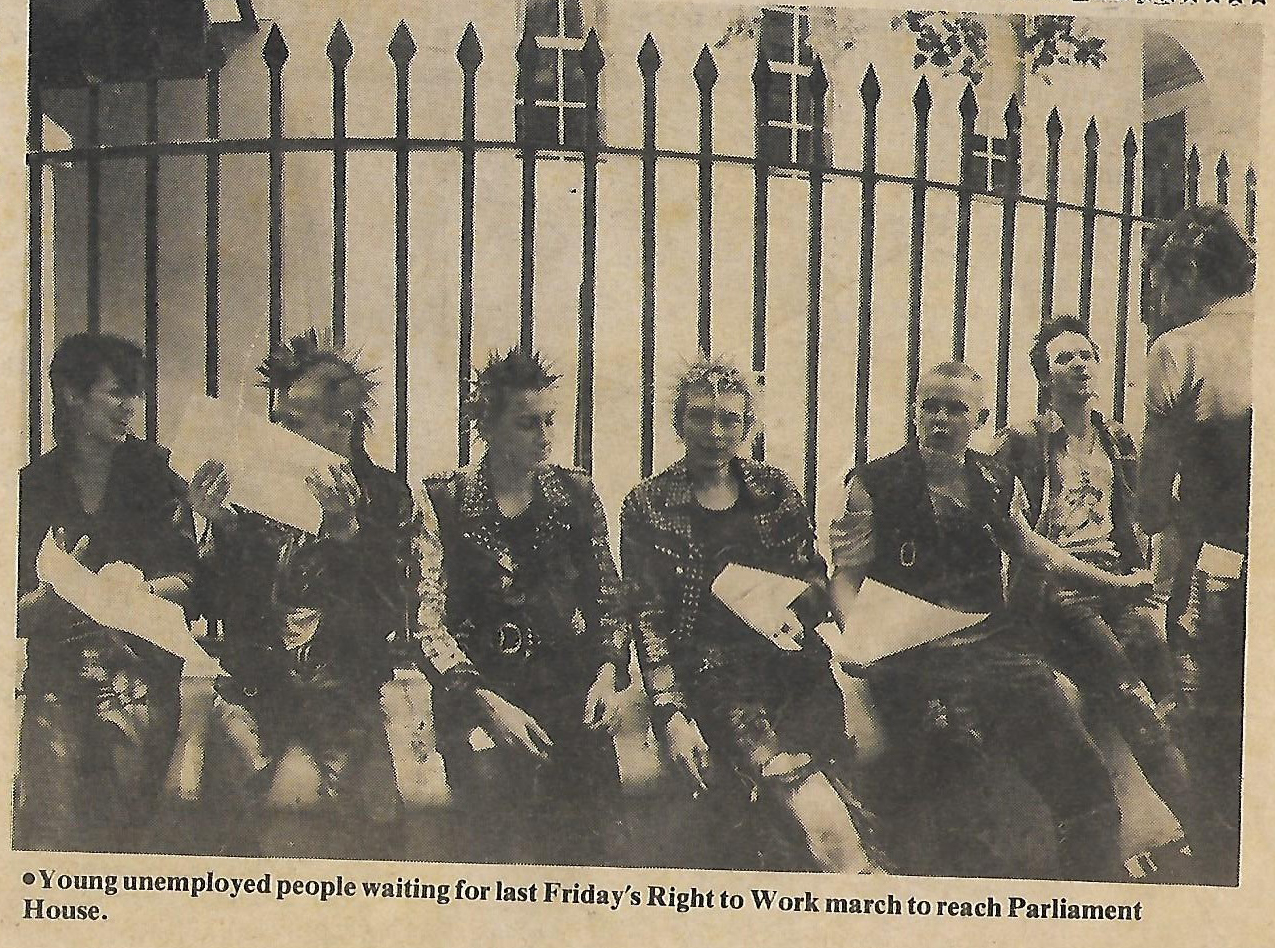

Interview: Young Communist Party activist

In 2016, my friend and comrade Alexander Brown interviewed me about some of my experiences as a young activist in the Communist Party of Australia during the late 1970s and early 1980s. In the interview we touch on a number of themes including my early involvement in the Young Communist Movement, my years as a full-time party cadre, tensions within the party between the national leadership and the South Coast District and the party’s relationship with international communist and resistance movements and domestic social movements. As Alexander said in his introduction to the original publication of the interview – “Where many histories of the CPA focus on machinations at the national level, Nick’s story reveals a living organisation with deep roots in the Wollongong labour movement and community that functioned as a family, if at times a dysfunctional one.” Alexander edited the transcript for clarity and length. I have edited it slightly for accuracy. The interview was first published on Dave Eden’s blog The Word From Struggle Street in 2018, divided into three parts. The first part was titled ‘The Party Was Like Our Family’, the second was titled ‘I saw myself as an activist, an organiser and a political cadre’ and the third was titled ‘they all knew that they didn’t agree on lots of, quite often very important things, but they managed to find the common’. Here they are together.

‘The Party Was Like Our Family’

Alexander: When did you join the Communist Party of Australia?

Nick: I joined the Communist Party of Australia in 1978. My recollection is that certainly when I applied I was 15. There was some concern about whether I could actually join as a 15-year-old because I don’t think a 15-year-old had joined before; so I think they might have waited until I turned 16 to allow me to become a member. That was November 1978. That’s my recollection.

Alexander: Why did you want to join the party?

Nick: Well, I had been in the Young Communist Movement before that, so I considered myself a communist as a member of the Young Communist Movement. Both of my parents were in the Communist Party of Great Britain when we lived in England and had joined the Communist Party of Australia when we came to Australia in 1974. My grandmother, my favourite person in the family, was a communist in Britain so, really, even before becoming active in the Young Communist Movement, I started to consider myself a communist. Not quite born a communist but certainly nurtured as a communist and so to me it just seemed like the thing to do. At the age of 15 I was already done with school. I was still there, but I wasn’t really participating in it. I was over with school and school to me seemed like a part of a capitalist society that I didn’t really want to be part of. I didn’t want to be involved in school and I didn’t want to be involved in the sort of society school was preparing me to be part of. I was thinking about becoming a full-time communist cadre and hoped to do that by leaving school, joining the party and becoming an activist, an active member of the Communist Party and working for the party in whatever way the party thought I could be the most useful.

Alexander: Was it the Young Communist League?

Nick: Movement, by this time it was called Movement. Eureka Youth League, was what it used to be called, but now it was, or certainly down here [in Wollongong], it was the Young Communist Movement. I think it was a sort of a reinvigoration of what had been the Eureka Youth League and sort of fallen into inactivity, or for some reason they had decided to change its name. I don’t think we were the only Young Communist Movement branch around, although we didn’t call ourselves a branch really. I think there was a few others around, but we certainly weren’t in contact with them.

How many of us were there? There was I suppose about eight, ten, ten of us, something like that, who were active. People would come in and go out but there was probably about eight to ten of us who were in it for a year or two.

Alexander: And that was in Wollongong?

Nick: That was in Wollongong, absolutely, yeah, Greater Wollongong. My brother and I were in it from this part of Wollongong, Mt. Keira. Most of the other young people were from further down south. And they were kids of party members but also there was three, I think, three young people who were children of left Labor Party members, whose parents wanted them to get a communist education in the movement rather than become active in a Young Labor branch or anything like that.

It started with a reading group, reading the Communist Manifesto. What would happen was that a group of us, and it was probably only half a dozen of us at the time, I think there was me and [my brother] Richard and Marlene, who was the daughter of the secretary of the wharfies (Waterside Workers’ Federation). There was a couple of Labor Party people’s daughters and one son and there was the metalworkers union [organiser] Steve’s daughter, so maybe seven. Those are the ones I remember definitely turning up pretty much every week. And the party organiser, Pete, would read a part of the Manifesto and then he would explain what the hell he was talking about. This may mean going, ‘bourgeoisie, OK bourgeoisie, blah blah blah’, or he may read a paragraph and then explain the paragraph. Up until not that long ago I still had the cassette, because he recorded the discussion, so you could take the cassette home if you were interested, which I was, and re-listen to it. It was supposed to be a discussion but, you know, most of the time it was Pete talking. There was some discussion and there was some, ‘OK you’ve explained bourgeoise and proletariat, but what about this?’ So that was the first thing we did.

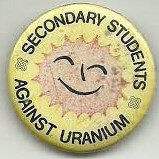

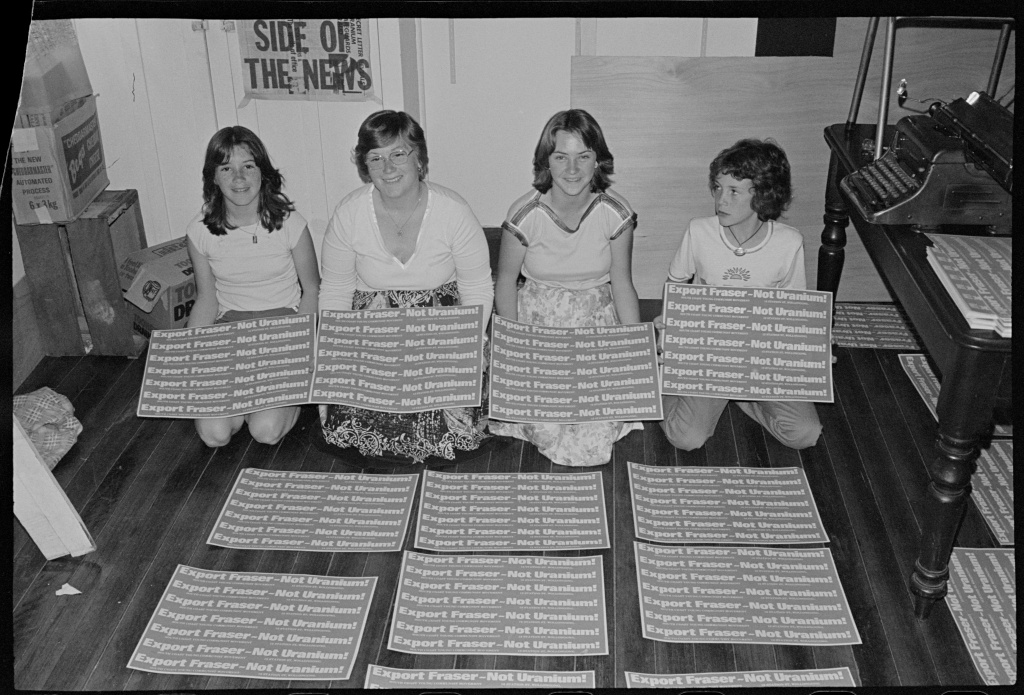

Then we would also have weekend camps at Minto where we would talk about all sorts of things and just have a good time. So, we would socialise and go swimming and play games, and get friendly with each other, as it turned out I ended up going-out with Fiona, the metalworkers’ organiser’s daughter, and those at the camp would occasionally have a drink or whatever. So, those were educational weekends, and there was education going on, as well as just socialising and becoming a group. And then, after a while, we started to decide on which issue we thought was the most important issue that we could organise around and we decided that was uranium mining. So we all agreed that that was the issue we thought was the most important at the time, that we actually were the most motivated to do something about and so we set up a Secondary Students Against Uranium Mining branch in Wollongong. We were the members initially, so it was a Communist Party front [laughter]—I think we might have talked about it in those terms at some stage—but that wasn’t our intent. We didn’t see it as a recruiting exercise, we saw it as an exercise in learning how to organise and getting other young people involved in politics around an issue that we knew young people were interested in and we were motivated to do stuff around. So that was our main activity, apart from educational stuff. Our main activity was organising Secondary Students Against Uranium Mining.

Alexander: So, what year is this roughly that you are talking about?

Nick: We are talking about ‘76/77 mainly.

Alexander: You said Secondary Students Against Uranium Mining ‘branch’, was that an existing organisation?

Nick: There was other Secondary Students Against Uranium Mining branches or groups–I’m not sure, I can’t remember exactly the term we used–around the country. Not a lot, but there was some. There was a Movement Against Uranium Mining, which was the sort of umbrella organisation for all of the groups taking action around uranium mining and many anti-nuclear groups. They’d encouraged the setting up of these groups of Secondary Students Against Uranium Mining and that had caught on elsewhere and so we could actually access badges and various merch and stuff, information materials and so forth from elsewhere. I think we got it straight from the Movement Against Uranium Mining. They sent it to us and we could then distribute it through schools and that’s what we did. You see, this way, we were school kids, yeah. I think even Richard, who was probably our youngest, were all in high school by then, or certainly he was just about to become a high school student. So, we’d take the stuff to school, badges and so forth, you’d sell the badges and give the information out. Have stickers, try and sneak them up in the toilets and whatever, that sort of thing. That’s where we spent most of our time, at school.

Alexander: So, at a broader level, was that movement associated with the Communist Party or was it just your local group that was particularly close to the Young Communist Movement or party organisations?

Nick: Look, I’m not aware. We weren’t really in contact with other Secondary Students Against Uranium Mining groups. We were sort of concentrating on doing grassroots stuff here in Wollongong. We didn’t get out and about that much as young people. Pete may have known more about it than we did, as the party organiser. But certainly it’s likely that there was some other branches or groups of Secondary Students Against Uranium Mining that were supported by the party. I don’t know that the Young Communist Movement was that involved elsewhere, but it’s quite possible they were. But there weren’t that many Young Communist Movement people anyway so, it’s likely that it also wasn’t the case or they were doing other things. You get a group of young people together and maybe there was something else going on in their region, or in their lives, that they thought was more important, that they were involved in.

Alexander: You just mentioned that Pete was the Young Communist Movement organiser, was he also the …?

Nick: He was the party organiser. So he wasn’t, you know officially, the Young Communist Movement organiser, there was no Young Communist Movement organiser, there was just the Young Communist Movement group and he was a part of that as the party organiser. If Pete hadn’t taken it upon himself to establish the group, there would be no group. So, it wasn’t like we were resentful that there was some old bloke there. We didn’t really consider him—he was in his twenties at the time so he wasn’t that old—and we liked him and we knew that without him there was nothing happening. It wasn’t like ‘oh they’ve imposed this on us’ or ‘he’s running the group or controlling us’ or whatever. We didn’t really know how to organise, we weren’t that motivated that we would have done it on our own and we were basically following what the party wanted because that was what we had grown up to expect to do. He was involved all the time, but he was pretty good with letting us do what we wanted to do, and encouraging us to do what we wanted to do. But obviously he was also supposed to be keeping an eye on us and making sure we were doing the right thing. Which sometimes he did, and sometimes he didn’t.

Alexander: Why did you want to go to the reading group in the first place? Why would you have decided to be involved? How did you find out about it?

Nick: Well, my parents were in the party, and I was already going to party events. The party would hold things, film nights those sorts of things. They were public events and anybody could go and I would go, and I’d talk to Pete, or I’d talk to other comrades, and they knew that I was interested. I think I wasn’t the only one and they realised, Pete being an organiser and a pretty good organiser, realised, we’ve got these young people who are interested, well let’s do something here and let’s start with the basics, which is sort of where I was at anyway. I had read the Communist Manifesto before we had that group but, it’s like I’d read it but what the hell!? You get the gist, but you want to know more than the gist. So that’s why I wanted to go because Pete could explain things that I didn’t understand and I could ask him questions about things I didn’t understand and I wanted to know.

Alexander: So those other people who were part of it. Would most of them have had a similar sort of trajectory do you think?

Nick: I think you sort of had fifty-fifty. I think fifty per cent was the same sort of thing and fifty per cent their parents had basically sent them. It was difficult for some of the Labor Party people because at the time, being close to the [Communist] party as a Labor Party member could lead to suspension or expulsion. It was a precarious situation for them. So how publicly they aligned themselves or involved themselves with party events and so forth could be difficult for them, especially since the two families I can think of the most had fairly senior positions within the local Labor Party. It wasn’t like they were just rank and file members. They had more to lose and the right-wing were more on their case and paying more attention to them. I think those young people hadn’t been in contact with the party. I hadn’t seen them around really as much, although you would see them at demonstrations and so forth and clearly there was friendship connections and social connections. I don’t know what was going on in their lives because I hadn’t come across them before but their families would have known comrades in the party and they would have socialised together and that sort of thing. I think basically their parents went, ‘we want you to go to this to learn’, so it was a form of schooling, rather than them being motivated to do it themselves.

Alexander: But in both cases they had a family connection to either the labour movement or the party in particular. They weren’t total rank outsiders to the culture of the Party and the movement.

Nick: Absolutely not. No, nobody was, no. And it never expanded beyond that. I don’t think there was ever any intention to. It was not a recruitment thing. We weren’t looking to recruit people to the Young Communist Movement. It was really seen as an educational thing for those who were already in the milieu and part of the culture and the party’s networks and so forth.

‘We are a communist family’

Alexander: That’s interesting because it implies that there was a real sort of family and cultural continuity or something like that with the way the party operated in Wollongong. Could you talk about that.

Nick: We often said, and often say, the party was like our family. It was very much, in Wollongong certainly, built around those sorts of familiar social connections and it was small enough to operate in that way. We are talking a hundred and something people, I think, as party members during these years we are talking about, the late 70s and early 80s. You can see that as a large but extended family. I remember Marlene, who was in the Young Communist Movement with me, she was at one stage wanting to write a book about being a communist child and how that works and we were talking about we could write it together because it is a very similar experience for children of communist party members. It was like, OK, we are a communist family. With active party members, that was your life. Being a communist was part of your life and so to be part of a communist family was to be a communist in many ways. Then the party, in a place like Wollongong, was an extension of that family so as you grew up you became more connected to that extended family. You can see that even with a fairly transient population, which Wollongong’s had over the last say hundred years or so, you can see the names, the family names, reappear, as you can in the party more generally, and party members’ children very often became party members and so forth. We thought of the party as a family. It wasn’t just that sort of hereditary handing down from generation to generation the communist legacy and the communist view of the world. It was also that for a family like ours and many families were the same, who’d come from elsewhere in the world, who had broken their ties with their extended families, this was a replacement. And so the party as a family very much operated as that sort of support network that your traditional family would offer you. So, Sally Bowen was like my grandmother. I’d left my grandmother behind in England. Sally Bowen, as the matriarch of the party, was our grandmother. Dave Bowen, her partner, was our grandfather. Pete wasn’t exactly a dad because he wasn’t quite old enough but there was those sorts of father figures and they would play that role. Not just was this about organising political struggle, but these were relationships of care. That was crucial to why I wanted to be more involved with the party, but also why the party worked so well in a place like Wollongong and why it was so powerful and influential. Because care was really crucial to the way we related to each other and the way we related to the class in general.

Alexander: Why do you think that worked so well in Wollongong?

Nick: Look, there’s all sorts of intangibles with Wollongong and the more I think about it the more I’m not sure. I think it does have something to do with the fact that a lot of people came here from elsewhere. That in many ways the city doesn’t have that long history and people came from all over the world and didn’t have those support networks and those caring relationships any more, that those had been broken and they tried to establish them in a different way. For me, communism is love and if you care about the class you care about other people and suffering and so forth, then when you are coming to a political realisation of the sort of society we live in and you are organising around communist ideas, however varied and diverse they are, somewhere there it has got to be about care and really it should be about love. Wollongong being a place where people came from all over the world, it is a hugely multicultural city, I can’t remember, I’ve seen different numbers at different times, but people have come from all over the place. The people who were attracted to the party, it wasn’t that they came here and they suddenly became communists. They were bringing communist traditions from all over the place. ‘The common’ of the communist traditions was caring and having those sorts of relationships.

But I think there is also the fact that Wollongong, if you look back at the history of the party in Wollongong, you are looking back to the 1920s, you are looking back to the Unemployed Workers Movement and the Unemployed Workers Movement for me is the key movement in the development of the Communist Party. In Wollongong, the Unemployed Workers Movement was incredibly important, much more important than in many parts of Australia. As somebody who has been active in unemployed people’s movements, I am aware of the crucial role of caring, supportive cooperative, collaborative relationships to survive day to day. Not just as some sort of political project but as a social project, about social relations of care and supporting each other, and that was crucial to the party’s formation in Wollongong and crucial to the history of the party’s culture. For me that was true, it’s true in other places, but in Wollongong compared with other places in Australia and elsewhere it was much more important. There was still people around when I was in the party who were involved in the Unemployed Workers Movement. They were still there and often they were the most respected matriarch or patriarch or whatever, if you are thinking of it as a family, the most respected long-term comrades. They had learned the basics of how to struggle and how to win, how to survive, their politics, via the Unemployed Workers Movement, and the impact of the Unemployed Workers Movement, and it was built around those sort of day-to-day caring relationships. Looking after each other. Having to rely on each other and the importance of how you treated other people. The Depression was the pivotal moment in that generation’s lives. It had a major impact on anybody who lived through that period and the Unemployed Workers Movement was the most important social movement at the time. Anybody really from that generation had internalised, if you like, that sort of survival strategy. A survival strategy which was about being really bloody nice and actually giving a shit about other people. For me they were the sort of people I wanted to become. I wanted to be like those people. As soon as you met them, you appreciated that they were different to most people that you met.

‘I saw myself as an activist, an organiser and a political cadre’

Alexander: So, around 15/16 you moved into full party membership or something along those lines. What changed. What did that involve?

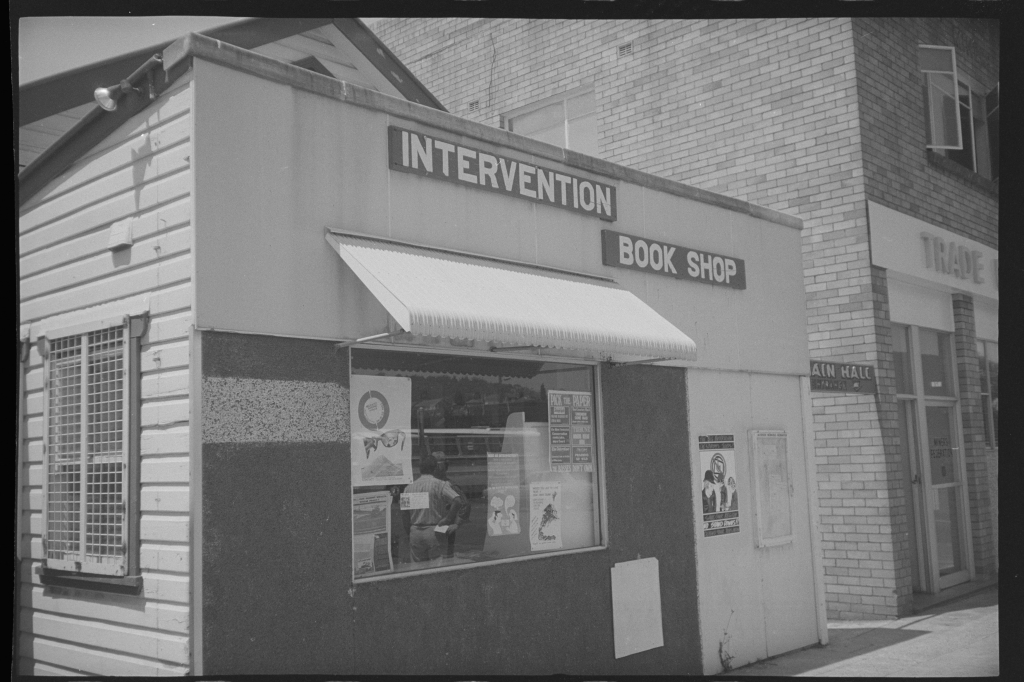

Nick: Well for me it happened at the same time as I became a full-time party cadre. There was no being a party member and then just going along to branch meetings and being involved in the branch activities. As I recall it, I got my card pretty much at the same time as I left school and went to work for the party full time. I did become a member of the Wollongong branch, which was the major branch, but only one of a whole number of branches. I’m trying to remember how many branches. There was a university branch, the Wollongong branch, the industrial branch, the waterside branch, there was the mining branch, a Yugoslav branch. Was there another one? I think there was half a dozen branches. Anyway, I was in the Wollongong branch. So obviously I went along to branch meetings, but as a full-time cadre really I was involved in all of the activities of all of the branches in different ways and I was working under the direction of the organiser, who was Pete. We had a bookshop worker, Viv, who did the accounts and did all of the admin at the party rooms. So there was three of us there. The party had an office in town, next door to the Trade Union Centre. The front of the building was the bookshop, then the office, then there was the printery on the side and then there was a small meeting room and the large Len Sutty hall at the back, where the major party activities would happen. So, I would work in the office helping out Pete with whatever, sometimes Viv with whatever. Obviously if people came in I’d be selling books and so forth. We’d go out and sell Tribune. We would produce party propaganda. There was an industrial bulletin, a waterside bulletin that came out, well the waterside bulletin came out every week, the industrial bulletin came out more irregularly than that. We would also put out miners bulletins. There was a whole range of activities we ran: fundraising stuff every week at the waterside pay line and at all the mine pay lines as well, which brought in a lot of money and we’d organise stuff around that. We had a press and I learned to operate the press. As time wore on, I became basically the printer. So I would do all of the party printing, all those bulletins and leaflets and whatever, on the offset press there. Occasionally I’d write for Tribune or write for the bulletins, the industrial bulletin or the waterside bulletin. But that was only occasionally. A lot of the stuff was just general stuff and Pete would say can you go and do this. We had a party car, a beaten-up V-dub, which was terrible because the handbrake didn’t work. When you drove out of the party offices, you were immediately on a hill, you didn’t have a handbrake. It taught me to drive, a bit. I mean I already had a license but still.

Alexander: So where was the bookshop? Are you talking about where the current trade union centre is?

Nick: It was in Lowden Square. So, the Trade Union Centre, I think it is still called Fred Moore House, where the [South Coast] Labour Council and so forth are now. That’s a new building, a relatively new building. In the ‘80s the old building was demolished. All the protests started there, out the front, same as they used to. They have for years. Lowden Square, that’s where the protest starts.

There was a building similar to that but smaller and next door was the party building, one storey. As I say, bookshop at the front and the Len Suttey hall was about half of it, which was out the back. There was an alleyway between the car repair joint next door and the party rooms so you didn’t have to go through the bookshop and the offices to get into the hall, you could just walk down the side and so when there was stuff on, usually at night, or meetings on, you could just walk down the side and use the hall. Other groups would use the hall, it wasn’t just Communist Party stuff. Some of the organisations that were close to the party would use it, some trade unions would use it, some social events, Australia-Vietnam Friendship Society film nights, that sort of thing.

Alexander: All those different branches you just mentioned, Wollongong branch, industrial branches, waterside branch etcetera, how were they connected to one another?

Nick: They were connected in that there was a South Coast District Committee. Each branch had representatives on the South Coast District Committee and they would meet once a month. I think branches met weekly, maybe some not quite weekly, but I think that was the basic structure. Branches meet weekly and the District Committee meets monthly. That’s my recollection. Maybe I’ve got the time wrong there. Maybe it wasn’t that often, but that was the basic structure. The reps would go to the South Coast District Committee. They would say, oh this is what the branch is doing etc. etc. They would discuss what the whole district was doing together. They would then obviously get information from the National Committee which would say this is what we want you to do. They’d discuss it. That would then be sent back to the branch. Then the reps would come and say OK, this is what the District Committee is doing, this is what the National Committee is doing. That’s how the communication and representation worked.

Alexander: As a full-timer, did you attend those meetings of the District Committee?